All Canaries Bear Watching

- Ranjan Kaul

- Feb 18, 2022

- 11 min read

by Ranjan Kaul

Exhibition entrance view, All Canaries Bear Watching, photo by Aakshat Sinha

Exhibition view, All Canaries Bear Watching, photo by Aakshat Sinha

The title of the ongoing exhibition, All Canaries Bear Watching, currently on display at the School of Arts and Aesthetics Gallery, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, is inspired by a book by Guinier and Torres [1] which draws attention to the practice of coal miners carrying a canary with them underground to assess the air quality inside the mines. If the air was so toxic that the fragile lungs of the tiny bird collapsed, then the miners would turn back. The authors remind us that the canary stands for the experiences of the marginalized: “All canaries bear watching. Our democratic future depends on it.”

Explaining the choice of the title for the exhibition, curator Premjish Achari notes: “The canary is a diagnostic metaphor foregrounded from the margins to proposed intersectional solutions against systems of oppression . . . The canary has to be kept alive to sing songs of possibilities and equality in an embattled time.” As part of a collaborative Indo-UK project organized under the aegis of GRID Heritage [2], the exhibition imagines an inclusive cultural sphere through the lens of gender, sexuality, class and race/ethnicity.

Selections from Sudharak Olwe's Photo Series.

Endangered Species: Malnutrition Stalks India's Children,

Including the Excluded: On Manual Scavenging,

In Search of Dignity and Justice: The untold story of Mumbai's conservancy workers,

Justice Delayed is Justice Denied: On Injustice for the Dalits

The exhibition features select expressions by a dozen artists and craft-persons from diverse backgrounds as also from a collective. Facing the entrance are the evocative works of acclaimed photographer, Sudharak Olwe, who, as part of his practice, documents the work and lives of sanitation workers, most of who belong to the Dalit community and who are compelled to earn their living through the menial work of manual scavenging. Despite government claims to the contrary, the inhuman practice of manual scavenging continues in India and other countries in South Asia. Displayed in the show are a representative selection of poignant family portraits of the workers pointing to the urgent need to provide sanitation workers the wherewithal that can ensure for them a life of dignity. It is however somewhat disappointing not to find photographs of manual scavenging in the selection.

Dayanita Singh, Myself Mona Ahmed, 2001

Exhibition view photo by Aakshat SInha

Dayanita Singh, Myself Mona Ahmed, 2001

Photographer-artist, Dayanita Singh’s oeuvre has an unwavering focus on gender and the Indian diaspora. As seen in her work on display, she has extended her art practice to book publishing, as experiments on alternate forms of producing and viewing photographs. Projected on the screen are pages from her book, Myself Mona Ahmed [3], containing successive photographic stills with running text documenting the life of the protagonist, Mona Ahmed, a eunuch. Dayanita Singh befriended Mona and photographed her life over a decade. Through the images we follow her daily rituals and her choices, such as choosing to live in a graveyard and adopting an orphan child, and her trials, such as being ostracized by her own kin, the anguish of being othered, coping with the loss of her adopted child. There are other intimate and personal glimpses of her taking a bath and how she finds solace and love among innocent, orphaned children and animals. Weaving together photography and story-telling in the unfolding of a life, this an evocative account of Mona’s inward journey and a reflection of an overlooked social reality of the third gender.

Malvika Raj, Quantum Leap, 2020

Malvika Raj, Into the Woods (left), 2020 and Sujata (right), 2014

Exhibition view photo by Aakshat SInha

Expectedly, we have art expressions from members belonging to the Dalit community. Malvika Raj is a trained Dalit-Ambedkarite artist from Patna who uses the traditional Madhubani art form to paint narratives reflecting Navayana Buddhism as formulated by Ambedkar. Given her thematic concerns, an image of the Buddha and a youthful-looking Ambedkar (who provided inspirational leadership to the Dalits towards their empowerment and assertion) are very much part of the narrative in Malvika’s work, Quantum Leap. To symbolize their struggle to reach their goal of social justice and equity, the artist uses the visual imagery of the members of the community raising hands of protest and climbing ropes and ladders, which are at times shown to be broken or snapped, signifying how arduous their task has been. I’ve a small quarrel regarding the title – I’m not convinced that theirs has been a “quantum” leap; while the Dalits have certainly got suffrage and rights under the Indian Constitution, they do continue to be othered and it will take a long while before they are accepted as equal citizens by the “self”, ie the established society. In the two works Into the Woods (2020) and Sujata (2020) the artist alludes to the "invisibilized" care of the Buddha by the Bahujan masses. As the story goes, Sujata, a farmer’s wife, fed the Buddha a bowl of kheer, a milk-rice desert, which gave the Buddha strength and sustenance to keep his body and soul together. While the milch cows are shown in the foreground, the Buddha himself is depicted in an unusual but befitting manner – penance-thinned and wearing a black beard.

Malti Rao: An Interview

The video interview with Malati Rao, a Dalit activist and singer, is a trifle disappointing. While it is heartening to hear her justifiably extol the greatness of Ambedkar, I was expecting for her to go on to make a mention of a few of his achievements and contributions to the Dalit cause, but she falls short of this.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar, Corona Pat (left), 2020 and Machher Biye / Wedding of Fish Pat (right), 2018

What makes the show markedly different from those we see in the renowned galleries are the works of artists from marginalized communities or those who use indigenous art forms. Additionally, these displays to a large extent answers the contentious question of when and how craft gets elevated to the status of art. To my mind, among other criteria, folk artists who innovate to depict contemporary social realities do acquire such a status. In this context, some months earlier on artamour we’d carried an article that featured Bhaskar Chitrakar (artist), a Patua painter from Kalighat who captures the Covid pandemic within the scope of the folk-art tradition. [3] This exhibition showcases the works of another two Patua artists. Dukhushaym Chitrakar, is a highly awarded, senior chitrakar belonging to the Naya village Patua community, who for generations has been involved with the pat-making style of painting on scrolls. In Machher Biye (or the fish-wedding pat), though keeping his art within the Patua art tradition which includes use of the fish motif, we see him consciously moving away from the brighter colours used by Patua artists. Painted in sepia tones using a limited and mature palette, the work is reminiscent of the muddy monsoon waters of Bengal. In the 1970s he started something unprecedented – training women to be independent chitrakars. Lutfa Chitrakar is one of them who has come to her own as an artist; she has been exhibited widely and has also won several awards. In the Patua Hindu community she belongs to, the artistic and performative skills are not traditionally passed onto the daughters. I’m informed that Lutfa lost both her parents at ten and was married off when she was fourteen and has been painting since then; a video shows her fully engrossed in preparing the paint, mixing vegetable dye with glue, for her next work. The Patua painters have been storytellers and they belong to both Hindu and Muslim communities in Bengal and other neighbouring states, symbolic of the syncretic culture of the region; while the Hindus traditionally painted gods and goddesses, the Muslim depicted fakirs and Muslim saints. For survival, they’ve shifted to portraying new themes in bright colours, which are bought by tourists. There are two contrasting works by Lutfa on display rendered in the typical Patua style, painted on paper and pasted onto cloth: one a retelling of the Ramayan epic, the Ramayan Pat, and the other depicting the most recent experience of the Covid pandemic. Both works reflect a feminist influence: while the former has Sita present in all but one of the imageries, the scenes related to the pandemic shows women characters in each imagery, be it mourning the death of dear ones, washing hands, or buying masks with the virus depicted as an omnipresent, teeth-bared monster who even inhabits the dead bodies. However, the dramatic visual elements are portrayed in a domesticated manner shorn of moralizing.

Lutfa Chitrakar, Ramayan Pat (right), 2021 and Covid Pat (left)

Close-ups of Lutfa Chitrakar's works

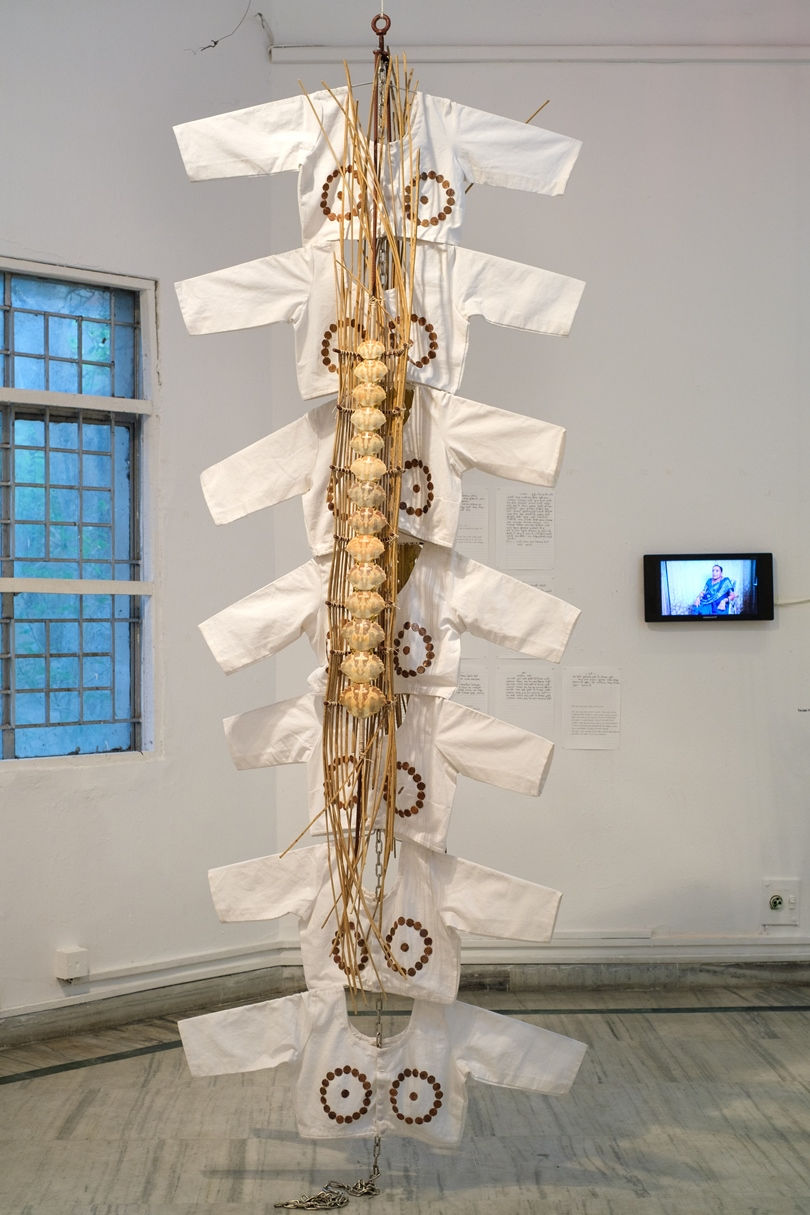

The Mumbai-based artist collective ‘Tandel Fund of Archives’ is a socially engaged archive and ethnographic pop-up museum of the Son Koli tribes (fisherfolk) of Mumbai that was co-founded by Parag Kamal Kashinath Tandel and Kadambari Koli Tandel. For some years now, they have been documenting the matriarchal Koli fishing community of Seven Islands (Mobai, now Mumbai), the oldest indigenous inhabitants of the city and creating art that draws attention to their issues. The intriguing installation, ‘Blouse Tax’ of Mobai / Mumbai, is inspired by a 16th century oral narrative. The Koli women traditionally wore the Kaashtha saree draped below the waist leaving their torsos uncovered. However, Portuguese merchants conspired with the local Maratha Brahmin community to introduce the blouse and compelled the Koli women to wear it, imposing the ‘blouse tax’ on those who refused to conform; later, the Koli community was coerced to convert to Christianity by the Portuguese missionaries in collaboration with the brahmins, who were bribed for each family’s conversion. The irony and assertion of the right to dress as one pleases is unmissable in this innovative installation that juxtaposes white blouses with round-shaped ‘moons’ of crab shells, using two species of crabs –the holy crab and the blood-spotted crab. While the former species has a symbolic narrative among the community in that it has a crucifix, the significance of the latter relates to a superstitious belief of the community which considers eating crabs sinful. The blouses are placed one below the other, as if on hangers, with a chain running behind, symbolizing the protest of the community against being “chained” by the conservative diktat. The installation mocks at colonial conservatism and at the same time asserts the right of indigenous women over their bodies.

Displayed alongside are videos of Dhavla folk songs, the oldest song tradition of the Koli community. While the original Dhavla poetry in Marathi is exhibited separately, we can see in the video a Dhavlarine (songstress) solemnizing a wedding, an old practice that has been significantly altered. Traditionally, as in the video documentation, Dhavlarines solemnized Koli marriages before Brahmanical influences changed the practice.

Tandel Fund of Archives, Blouse Tax of Mobai / Mumbai, 2021

Tandel Fund of Archives, Dhavlarines: Koli (Fisherfolk) Songstresses of Mobai / Mumbai

Ranjeeta Kumari is a conceptual artist concerned with creating a visual identity of the marginalized. Her work titled Threads is inspired by the poetry of resistance of Bhikari Thakur and the Sujani embroidery work of women, where old clothes in the household are repurposed into brilliantly coloured patchwork quilts. Through the framed rhythmic and lyrical patterning of recycled saris of households, she questions the aesthetics of labour, thus elevating the embroidery skill to the status of art.

The Group of Dushadh Paintings from the collection of art academic Meena Singh is significant in that while Mithila art of the elite Brahmin and Kayastha women artists has been as “high art”, the art practices of the Dushadh peasant community and of other lower castes (Chamar, Mali, Nata, etc. who share a common tradition with the Dushadhs) is labelled as subaltern art. Meena Singh’s note from her book on Dushadh art gives us an interesting insight into this unique art tradition: “The popularity of tattooing amongst the lower caste has been primary reason for adoption of its form and style by Dushadh artists. It is in the paintings reflecting the social life that the close relationship between artists and their environment can be discerned.” [5]

Ranjeeta Kumari, Portraits of Women (Poetry of Resistance),

40 frames of collected old saris, 2018-2021

Leading conceptual contemporary artist, Shilpa Gupta’s 'Drawings Made In Dark' series focusses on the fluid borders of Bengal where she traces clandestine routes and flow of goods which persists at late nights despite the near completion of the world’s longest border fence between India and Bangladesh. The work is a sharp comment on how artificially imposed human borders have divided the peoples of Bengal. Another of her works on display is the India Map which is part of her series, 'Map Tracings' – outline maps made up of metal tubing, twisted to form three-dimensional linear sculptures. Using shadow and illusion in negative space to create an oscillation between recognition and perplexity in the minds of viewers, they modify the familiar outlines of nation-states into uncharacteristic forms. Depending on our movement and orientation when viewing the work, the recognizable shape of the map warps our vision, reminding us that the nation is an artificial construct, and what it maps is the way it imagines itself.

Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2015

Shilpa Gupta, Map Tracing #1-N, 2012 – Ongoing

Rakhi Peswani’s art practice explores various discursive and material aspects of hand-made craft and its nuanced associations as language. Her series of drawings, ‘Inflections (Reflections on Land)’ juxtaposes natural pigments, traditionally used in dyeing, as reflections of primal stains. According to her, the drawings frame sensations from materiality and social processes of the body; also, they frame prevailing notions of femininity. Her imagery is surreal and nebulous: while in one work the lying body is half in and half out, with a gutter prominent in the foreground, the latter may be interpreted as memory or dreaming with a distinct suggestion of the “stains” of menstrual fluid. Taken together, both works suggest the fragility and vulnerability of the human body.

Rakhi Peswani, Inflections (Reflections of Land), 2019

Mithu Sen is a conceptual artist who uses varied and multidisciplinary art expressions. A multi-media installation titled I have only one language; it is not mine engages with the idea of radical hospitality, exploring in the process the limitations of language and the possibility of dialogue beyond it. For the project Sen spent several days at a home for minor female orphans and victims of sexual and emotional abuse in Kerala and lived their life. Interacting with children as the alter-identity ‘Mago’— a seemingly homeless person – who speaks gibberish, does not understand the concept of time and is in a state of transit. Using filters on the video footage, she renders the images as blurry rust lines against a bluish-green backdrop to make for a more compelling and dramatic viewing.

Mithu Sen, I have only one language; it is not mine, 2014,

Duration: As long as you want to watch, video from the exhibition by Aakshat SInha

Ita Mehrotra is a visual artist, researcher and currently Director of Artreach India, a not-for-profit organization that works at the intersections of art, inclusive education and community development. She beautifully captures a graphic street-level view of the peaceful and dignified agitation that took place in the winter of December 2019 in the form of a book titled Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection [6]; pages from which are displayed on the screen in the exhibition. (I had featured her book in an essay on how artists have responded to recent socio-political evens on artamour.[7]) Now seen alive on the screen monitor, the work is a visual narrative of the poignant, courageous and heroic stories of the ordinary women of Shaheen Bagh, which catalyzed a pan-Indian political movement against the CAA and NRC. Mehrotra creatively depicts the inspirational story how the protest grew into a large collective movement. We see the indomitable courage of the women who remained undaunted in the face of brazen targeting, by speaking up fearlessly, raising personal stakes and by not retracting their stance of dissent.

Ita Mehrotra, Panels from Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection, 2021

Taken as a whole, the exhibition compels us to revisit current art discourses, particularly in terms of the vexed relationship between art and craft practices. It projects marginality beyond victimhood and encourages the marginalized, who have been oppressed for historical reasons, to assert their identity through creative aesthetic expression. As Premjish Achari puts it, the exhibition opens up a space “to engage in discussing uncomfortable but relevant topics . . . the role of heritage in nation branding, the erasure of caste as an operative term . . . and the unresolved association between politics and aesthetics.” If I was allowed one complaint, it would be that the selection could have been even more representative, and include selections from the “canaries” of other regions, particularly the states in southern India.

Exhibition views, All Canaries Bear Watching, photos by Aakshat Sinha

References and Notes

[1] Lani Guinier and Gerald Torres, The Miner’s Canary: Enlisting Race, Resisting Power, Transforming Democracy, Harvard University Press, 2003.

[2] The exhibition is organized by GRID Heritage in collaboration with JNU, Asia Centre, University of Sussex, ICHR (India), South Asia Institute SOAS, ACHR (UK) and The Jena Foundation.

[3] Dayanita Singh, Myself Mona Ahmed, Scalo, 2001.

[4] Ritika Ganguly, “The Coronavirus Touches the Brush of the Patua Painter of Kalighat”, artamour, 1 November, 2020.

[5] Meena Singh, “Subalternism in the Studies in Indian Art: An Argument concerning Dushadh ‘Madhubani’ Paintings” in Towards a New Art History: Studies in Indian Art edited by Shivaji Panikkar, Parul Dave Mukherji and Deeptha Achar, New Delhi: DK Printworld, 2003 (pp. 288-293).

[6] Ita Mehrotra, Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection, Yoda Press, 2021.

The exhibition will remain open till 27 March 2022.

(All the images are courtesy of the respective artists, GRID Heritage Project and photographs by Nikhil Mishra, unless mentioned otherwise.)

Ranjan Kaul is an artist, art writer, author and Founding Partner of artamour.

His art can be viewed on www.ranjankaul.com

Comments