Art of Response: On Canvas, Paper, Screen

- Ranjan Kaul

- Aug 14, 2021

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 21, 2021

Part One

by Ranjan Kaul

Throughout history, artists and writers have responded to social and political events – be they war, catastrophe, deep-rooted social prejudices, injustice, brutality, or oppression against women. In the world of art, there is no better example than Picasso’s well-known anti-war work, Guernica, which was his response to the Nazi bombing of the Basque city of Guernica; perhaps less known, less nuanced, but equally powerful is his Massacre in Korea, a painting depicting a group of women and children facing a faceless firing squad. Another of my favourite works is Peter Blume’s The Eternal City, where he juxtaposed an image of a glaring Mussolini with a small effigy of Christ covered with trinkets by his worshippers in the backdrop. Completed in 1937, the unmissable irony in his work and its unambiguous message is particularly relevant in the contemporary world where we see fascist forces rearing their ugly heads.

While social and political events do provide ideas, themes and other realities for art to express or portray, it is a matter of conjecture as to the extent the visual arts can or do impact society. In the Indian context, with few people visiting galleries, and limited art events taking place on the streets or in public spaces, it would be wishful thinking that a painting, installation or sculpture will so affect society as to bring about any major societal change. However, the silver screen and now more recently OTT platforms have shown films and serials that have contributed significantly as powerful influencers of change in mass consciousness.

On the flip side, there will be many who argue that the visual arts are essentially a means of self-expression, but they too would concede that some genres of the visual arts do reflect social and political concerns in their content. Without getting into this never-ending debate, here I'd like to focus on a selection of Indian artists who are breaking the mould – creating art in response to socio-political events and situations and who follow their conviction to create art regardless of market diktats.

Speaking specifically about India, we’ve had several artists like Chittaprosad Bhattacharya who made poignant woodcuts depicting human suffering and deprivation in response to the Bengal Famine and floods or Satish Gujral and Krishen Khanna who painted stirring images of the Partition; in more recent times, internationally acclaimed artists such as Arpita Singh, Anita Dube, Vivan Sundaram, Nalini Malani, Shilpa Gupta and art collectives like Sahmat and the Raqs Collective have depicted societal concerns in their own individual styles. For this essay, I’ve selected some other equally talented and committed Indian artists, some well-known and others perhaps less so but who certainly warrant far greater viewing and discussion.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a traumatic time for all sections of society, but more so for the disadvantaged and marginalized. In my essay titled The Art and the Pandemic I’d explored the works of several artists down the ages who’d responded to wars and pandemics like the Black Death, Spanish Flu and the AIDS virus. So it isn’t surprising that some Indian artists have created works centred around Covid-19 and its after-effects – unemployment, the plight of migrant workers, deaths, inept handling of the pandemic by the state, and so on.

Sanjeev Sonpimpare is one such artist. A multi-disciplinary artist based in Mumbai, who during the lockdown and in spite of limited availability of resources and materials, created the series titled “Lockdown 2020” that reflects the impact of the pandemic and the state response. The physical isolation owing to the lockdown gave him an opportunity to contemplate on the times we’re all going through and create works that are, as he says, “a manifestation and an expression in visual form”.

Blue 2 (Divider)

In Blue 2 (Divider) we see two figures in the foreground in deep contemplation and in the words of Sonpimpare, “with the inner dimensions of the mind fertile and empty to sow new seeds.” Those who are familiar with his work will immediately notice the use of the blue colour as reflective of the socio-political environment where democracy becomes a mockery seen against the light of the persistence of a legacy of caste discrimination and ostracism. The presence of the divider in the middle, consisting of what appear like agricultural digging implements criss-crossing each other, mimicking as it were the arms of the two people on either side, mirrors the prevailing divisiveness in society. In another work, the artist speaks of loneliness that has been thrust upon us, but here too, privacy has been invaded with the prominent presence of the “tree of surveillance” with its “branches and leaves” of cameras and surveillance devices: “Physical Distancing: You are being watched 24 x 7”. On the ground the snooping tree casts a pale shadow of a money plant, reflecting the dwindling economy.

Tree of Surveillance

The sudden lockdown imposed without notice saw lakhs of migrant workers trudging thousands of kilometres to their villages and towns. Some lost their lives either from hunger, exhaustion or infection or from accidents. The “state” remains in denial and continues the refrain of “NO DATA” as seen in another of the artist’s work shown below; the significance and irony in his work cannot be seen merely in relation to migrant deaths – we cannot help but relate it to the more recent state response to the number who died owing to lack of oxygen. Sonpimpare here contrasts the tragic plight of migrants against the continuation of grand urban projects such as the metros and highways as shown by the black-and-yellow striped barricades, which ironically are built by the very same migrants.

Another of his recent work again comments on this so-called “development” and modernity such as radar technology. Alongside this is the disturbing persistence of superstition and irrational beliefs; the artist depicts this symbolically by the lemon and chillies traditionally hung on entrance doors to ward off evil, and also by appropriating the traditional motif of clouds from Indian miniature painting.

NO DATA

Atta Chakki (see below) symbolizes the “grind of life” and raises basic questions about hunger and the right for food. The work points to the hard reality that while the granaries are overflowing, resources are not reaching the hungry; here, grain may be seen as a wider metaphor for inequitable distribution of resources. In the right foreground we see the presence of a multi-handed, multi-headed mythological entity snatching away food from the have-nots. In the Game of Chess being played between the marginalized “minorities” and the “ruling class” depicted by the pawn and the skin of news stories and the towering king piece respectively, the expressive faces unambiguously reveal who is winning.

Atta Chakki

Game of Chess

Other works of Sanjeev Sonpimpare from the "Lockdown 2020" series

Born in Kolkata and brought up in Bihar and Delhi, Soumen Bhowmick is a visual artist, independent art lecturer and also a cultural activist and keen blogger. Through his drawings and paintings he portrays his understanding of the socio-political climate with deep sensitivity and a unique sensibility. Soumen’s book of drawings, titled Manus, contains 725 amazing, black-and-white drawings – quirky, satirical, macabre, playful, unsettling – wherein he uses skeletal frames, bones, muscle tissue, daggers, and other unusual symbols to depict human emotion.

Drawings by Soumen Bhowmick from his book titled Manus

In his first solo show in 2010 at Triveni Kala Sangam, Soumen began with a bright and colourful palette in his series titled “Circus of the Absurd”, where he used the device of the clown, mouth agape and tongue out, to reflect the absurdity of the socio-economic environment where the hapless individual finds themselves compelled to do tricks to ingratiate the powers that be. The use of arrows and bones in the series have increasingly became a predominant part of his oeuvre as seen above in his drawings in Manus and later where he moved to a more muted monochrome palette using mixed media, including coffee, for his later successive series titled Head Tale, Chronicles of V, Silly Times, Monochrome Days and his ongoing series Prototypes of Fear.

Works from Circus of the Absurd

Describing his work, Soumen says, “My art is a pictorial documentation of my emotion at that present moment, which is primarily influenced by the socio-political happenings in my immediate surroundings and also globally. What I absorb with my senses is what I create with utmost honesty. I'd rather call myself a visual-biographer of humanity, who uses his pen and brush to document life's intricacies on paper or canvas.”

His monochromatic works By Air and Kingdom of Bones shown below were both done during the Pandemic using coffee as a medium, possibly because of lack of art resources. By Air gives us a powerful view of humanity enslaved by Covid-19, depicted as confined in an aircraft, symbolizing the airborne nature of the virus. Perhaps not the artist’s intent, one could also interpret the work as corpses floating in air because there is little space left for burials or cremation on land. In a related work, Kingdom of Bones, a gloating king wears a crown of the skeletal remains of the dead, while in another a gruesome fate awaits those who dissent in the World Order.

By Air

Kingdom of Bones

World Order and other works by Soumen Bhowmick

(Please use the left-right arrows to navigate the slideshow)

Pramod Prakash is an artist who consciously challenges accepted aesthetic norms of art and beauty to depict social realities as he sees them. Recently, we had a very engaging discussion on Clubhouse @artamour on the subject of what constitutes good art and the importance of meaning in art.

As Pramod says, “Some people talk idealistically about how beautiful the drawing and colours should be. The real side of life may be negative, and for me this carries with it its own beauty . . . My work reflects this dark and grim side of life. I’ve no problem if I receive flak for not being aesthetic enough. My paintings reflect the existing social order. The outside of the house may appear beautiful and well decorated, but what I wish to showcase through my work is not the exterior – for me, that is insignificant. Rather, what interests me, is the ‘inside’ and the ‘hollowness’ of it all.”

Charcoal works and paintings by Pramod Prakash

(Please use the left-right arrows to navigate the slideshow)

“My paintings reflect ‘space and time’ very clearly,” the artist adds. “The specificity of time also shows up in my work. After the lockdown, migrant labour walked miles and miles from the big cities to their homes with no support, sometimes without food or shelter . . . This human tragedy touched my heart.”

He says that his father, a freedom fighter, said the fight for Independence was primarily to resolve fundamental social issues. However, after so many years of Independence we see that a completely different social and cultural edifice has been constructed where human well-being has been neglected and the feudal structure persists alongside superstitious religious beliefs. Pramod says that the kind of misinterpreted “nationalist religiosity” we see today can be destructive if not understood properly.

It is not easy to fathom the artist’s deeply sentient works – we need to go deeper into their inner core to fully comprehend their meaning. As Pramod says, "I paint the consciousness of every day, every moment.” There are psychological elements in his complex works, where he uses animal and bird imagery to symbolize carnal desires, which he says gets repressed owing to misunderstood religiosity; as represented by quick thin brushstrokes of a semblance of a Hindu temple with a triangular flag, a mere hint of a religious structure, or a bovine head.

Well-known, Goa-based graphic artist and designer, Orijit Sen, has in recent years been creating visual satire which he regularly disseminates in the social media. He is best known for publishing India’s first graphic novel, River of Stories, where he highlighted the damaging consequences of the Sardar Sarovar Dam, which was constructed in spite of huge resistance and protests. In his more recent art practice he has been making satirical “political posters” using wit, irony and wry humour that are scathing attacks on the current political dispensation. Sen says that he is “attuned to the multiple meanings that emerge from the interplay of text and images” in his posters. The first poster on the left below is a commentary on the current regime in office, which he views as one that has enabled a tectonic, regressive shift from civilized humans to sycophantic, servile sheep in the short span of seven years.

The one on the right above narrates the tale of two contrasting Parliaments: one, where citizens are depicted as “upholders” of democracy; and the second that seems to depict the opposition representatives gagged and bound. In another work on the right below, the crumbling iconic India Gate representing the dire state of the economy is foregrounded with Yama, the god of death, on a Sensex bull run. “Talking about his political position, Sen says, “I do take responsibility for what I create. I admire artists who do not flinch . . .” The poster on the left below, advertising a cure for "Fascistitis", is self-explanatory and equally bold and thought-provoking.

Talking about the role of art, Sen says that “art needs to be relevant to people, to the society it is coming out of. I don’t think that all art should be overly political but a lot of art is irrelevant to the larger public.”

Cinema is often regarded as a synthesis of many arts. Apart from films designed for pure entertainment (akin to “decorative” painting to adorn walls of the non-discerning) and making big bucks, there have been film-makers who've made meaningful cinema reflecting the hopes, aspirations, fears, prejudices and concerns of society. Indian cinema of the 1950s and 1960s reflected the feudal order: Thakurs, mill-owners and landlords were portrayed as oppressive villains, such as in Do Bigha Zameen and Mother India. More recently, Tamil cinema in particular has offered insights into the social realities of Dalits, their misery and oppression, such as in Virumandi, Thevar Magan and Chinna Gounder. While Tamil Nadu became the home of the powerful non-Brahmin movement, changes in Tamil cinema became more pronounced in the wake of the Mandal Commission Report. Pa Ranjith’s Pariyerum Perumal, using modern rap with folk forms provides us gory details of attacks on Dalits. His other notable works include Kabali and Kaala (in the latter film, superstar Rajinikant plays a Dalit). More recently, Mari Selvaraj’s film Karnan is again a powerful tale of defiance against caste-based oppression.

Amongst the ensemble of Indian cinema reflecting caste divides is the iconic Marathi film Sairat. The Bollywood adaptation, unsurprisingly, chose to drop the caste element, thus giving a most superficial complexion to the narrative. In fact, Bollywood’s small-town heroes are almost always upper caste – Sharma, Shukla, Dubey, Pandey; we are unable to recall a superstar who has played a Dalit on the screen. While films such as Achhut Kanya and Sujata did present the plight of Dalit women, the Dalit remained the "invisible other" for a long time till “art cinema” came on the silver screen: Shyam Benegal’s Ankur focusses on female sexuality, debauchery and caste divide, while Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh portrays the ordeals of a tribal protagonist in a highly stratified society. Jait re Jait, a Marathi film, depicts the struggles of two tribals who stay together despite the tribulations of their community, while the Kannada film Chomana Dudi (Choma’s Drum) brings to the screen the struggles of a bonded labourer who dreamed of buying his own land.

Satyajit Ray’s Sadgati (Deliverance) based on Premchand’s story for Doordarshan is a somewhat pitiful depiction of the issue of caste; in the final moments of the film a caste-ridden corpse is dumped by the Brahmin priest into a field of rotting corpses. It is pertinent to point out that the film gives only a sympathetic portrayal of a Dalit, whereas Tamil films, particularly the more contemporary ones, have depicted angst and assertion with deep empathy and understanding. In this regard, Shekhar Kapoor’s Bandit Queen remains one of the best contemporary imaginings of a casteist society.

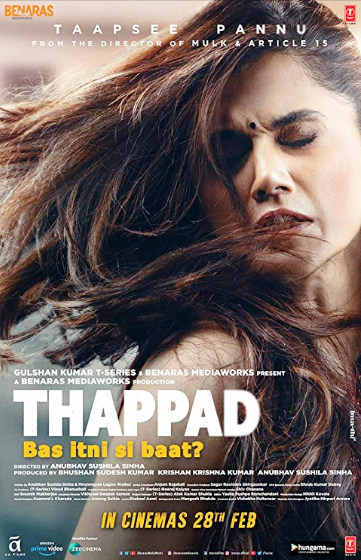

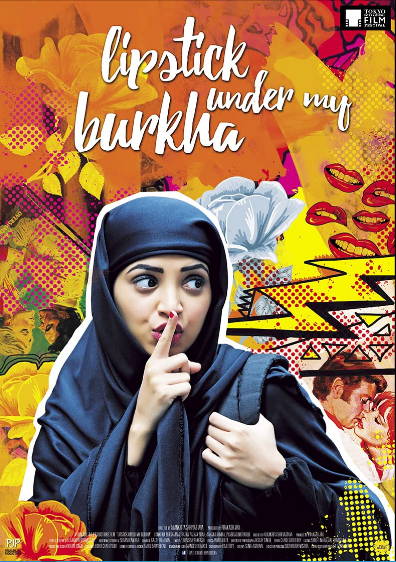

In Bollywood, such films have been few and far between and only a few such as Newton, Manjhi – The Mountain Man and Masaan portray Dalits as heroic characters. Film-makers have however been less circumspect with regard to themes that relate to gender equality, gay rights and sexuality with films such as Aligarh, My Brother . . . Nikhil, Chhapaak, Thappad and Lipstick under My Burkha.

In Part Two of the essay, we will examine visual art practice as seen in the genre of performance art, in public spaces and on protest sites. Do watch out for that!

(Cover image: A work by Sanjeev Sonpimpare)

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to the artists Sanjeev Sonpimpare, Soumen Bhowmick, Pramod Prakash and Orijit Sen, who took out time to share their works and discuss them with me. I would also like to thank my wife and film buff, Dr Rekha Kaul, for her valuable inputs and insights on the Indian cinema part of the essay.

Ranjan Kaul is an artist, art writer, author and Founding Partner of artamour.

Comments