The Dotted World of the Bhils

- Shantala Palat

- Feb 20, 2021

- 5 min read

by Shantala Palat

Bhuri Bai of Pitol’s recent award, the prestigious Padma Shri, is yet another feather in her cap and her achievements signal renewed hope and optimism in the world of Bhils and their art. The young Bhil artist Sher Singh Bhabhor is ecstatic as he sees it as a wonderful and proud moment for his community.

(Image courtesy of the artist Sher Singh Bhabhor)

Bhil art has its own rich heritage, culture and history. As the third largest tribe in India, the Bhil tribe belongs to the Western and Central belts, namely, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tripura, Andhra Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. The Bhil tribe differs across each region for their local gods, songs, customs and dances.

The word ‘Bhil’ itself has several meanings— brave and martial (in Sanskrit), ‘bow’ in Dravidian terminology and in Tamil, ‘bowman’. It is thus no wonder that the tribe has traced their lineage to Eklavya, the skilled archer in the Mahabharata, while some scholars also claim that Valmiki, the author of Ramayana was a Bhil himself. The Bhil archers of the Alirajpur district (Madhya Pradesh) continue to use the no-thumb tradition while learning archery. It is a symbolic mark of respect for their hero, Eklavya, and protest against the injustice meted out by Dronarcharya and Arjun. The Bhils had been great warriors who rebelled against the Mughals, Marathas and the British rulers. There are historical accounts of how four hundred Bhil warriors helped Maharana Pratap in the Battle of Haldighati against the Mughals. The relationship between the warriors and the king was so deep that he was even fondly called ‘Kika’ (son) by them and their contribution has been depicted on the Mewar Royal Coat of Arms (Udaipur).

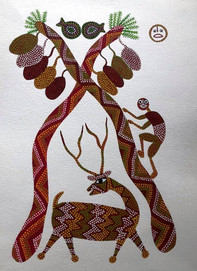

Art by Sher Singh Bhabhor

(Images courtesy of Bhilart site)

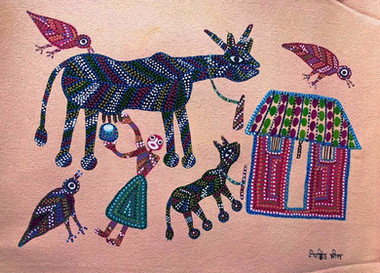

Bhil art has a naïve, folkish touch to their paintings. As they are farmers and agricultural labourers, the images revolve around nature, the harvest, rain and the gods responsible for a good crop. Their brightly coloured animals, trees and people are inundated with sets of even dots all over the painted surface. Their distinctive dotted style, akin to the pointillism technique of the French Impressionists in the 1880s, is prominent in the artworks. Independent scholar ,Urmila Banu, points out that the dots serve two functions— one, for possible decorative purposes, and the second, to represent the maize and raindrops often associated with a good harvest. In addition, as each dot was painted, the artists were also paying their respect to the ancestors and the gods, specifically Babo Pithoro or Pithoro Dev. Sher Singh recalls the elaborate parampara Pithora paintings done on the mud walls of the houses. The colour palette was largely natural colours (turmeric, flowers, seeds, mitti) obtained from their surroundings while neem twigs were used as brushes for the clay walls of the house. The rituals associated with Pithoro Dev and his horse were immensely important to the Bhils. Worshipping Him was incumbent to the god showering them with blessings and rain for their fields.

Art by Ram Singh

(Images courtesy of Bhilart site)

Interestingly, Bhil and Australian aboriginal art share the common characteristics of dot painting in their works. One reason for these similarities could be dated to an older idea about the migration of people to different parts of the world in ancient times. India and Australia were once part of a large ‘supercontinent’ known as Gondwana. It is possible that certain populations migrated to Australia, carrying their art and culture with them. As Huxley [1] pointed out, “the only people out of Australia who present the chief characteristics of the Australians in a well-marked form are the so-called hill-tribes who inhabit the interior of the Dekhan, in Hindostan.” Bulu Imam and Dr Raghvendra Rao also believe that the Indians may have arrived in Australia nearly four thousand years ago [2,3].

Art by Subhash Bheel, Acrylic on Canvas

(Images courtesy of Urmila Bano)

Bhagoria by Subhash Bheel, Acrylic on Canvas

(Image courtesy of Urmila Bano)

Art by Lado Bai, Acrylic on Paper

(Images courtesy of Urmila Bano)

Art by Lado Bai, Acrylic on Canvas

(Image courtesy of Urmila Bano)

Art by Gangu Bai, Acrylic on Canvas

(Images courtesy of Urmila Bano)

Bhuri Bai is often credited for being the first Bhil to paint on paper and stepping outside the ritualistic world of Pithora art. Notably, the wall paintings had often been done by men while the women folk looked on[4]. Her son Subhash Bhil and her daughter-in-law are also Bhil artists, while Bhuri Bai continues to teach and train her people on the nuances of the art form. Meanwhile, Lado Bai has made her quiet mark with her vivid animals and birds that perch on them. The world of Ram Singh, Sher Singh Babhor and his mother, Bhuri Bai Jher (not to be confused with Padma Shri awardee Bhuri Bai) are peopled with delightful and everyday scenes – be it the grazing of cattle, festivities or nature in her abundance. The open mouths, thick eyebrows and long noses of the human figures are strongly reminiscent of the African face jugs. The forms are childlike and innocent, as though unschooled in any training of art.

Sher Singh's mother, Bhuri Bai Jher, making a mud relief

(Image courtesy of the artist Sher Singh Bhabhor)

(Images courtesy of the artist Sher Singh Bhabhor)

As much as the Bhil paintings continue to enthral us with their vivid dots and bright colours, struggle for survival looms in the shadows. The pandemic made things harder especially for the lesser-known artists as their regular incomes had dried up and they struggled to make ends meet. There is an oft-posed question as to why there has been a sluggish interest in the art form and why it has not flourished as well as the others. The reasons could be multi-fold. Firstly, the highly ritualistic Pithora paintings and the several decades of separating from the fixed world of tradition had been a slow and gradual process. Secondly, the severe repression acts by the British rulers (1846, 1857-58 and 1868) and classifying the tribe under the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871 [5] during pre-Independence had led to years of crushing poverty and stereotyping the tribe. It also could be the perceived lack of a sophisticated style as compared with its counterparts like Gond art, or simply, that it was not as vigorously promoted as the others. Bhuri Bai’s Padma Shri is indeed a silver lining for this oldest tribe that has been much overshadowed by other successful folk and tribal art forms in spite of its rich heritage.

References

Thomas Henry Huxley, On the Geographical Distribution of the Chief Modifications of Mankind on JSTOR.

Darren Curnoe, An ancient Australian connection to India? UNSW Newsroom, March 2016.

SBS Language | The Story Untold - The links between Australian Aboriginal and Indian tribes.

Bhuri Bai Bhil, Dotted Lines— A visual autobiography of an artist, with Debjani Mukherjee, Katha, 2019

Wikipedia, Bhil people - Wikipedia.

www.Bhilart.com - The Bhils - Bhil Art

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Urmila Banu for her generous time, sharing her valuable knowledge and giving permission to use the Bhil paintings for the article. I am equally indebted to Professor Nina Sabnani for her guidance and permission to use the images from Bhilart.com. And above all, Bhil artist Sher Singh Babhor and his gentle painted world of colourful birds, fish, trees and his beloved festivals.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Shantala Palat is an artist, art educator and an ardent lover of folk and

tribal art.