On the Threshold of Time 8: Unseen

- Aakshat Sinha

- Nov 21, 2020

- 13 min read

by Aakshat Sinha

Art Heritage, founded in 1977 in New Delhi by the eminent couple Ebrahim and Roshen Alkazi, has been organizing an annual show called On the Threshold of Time to feature young and emerging artists for eight years running. The exhibition has been held usually at the end of their art season – March-May every year. However, as India entered the lockdown phase in March this year owing to the pandemic, all art activities ground to a halt. With norms getting slowly relaxed, the gallery kick-started the new season with the pending show, adhering to the specified safety guidelines. On an average, the show has featured 13-14 upcoming artists but this year works of only five artists are on display – Bhuwal Prasad, Natasha Sachdeva, Amit Saha, Tarun Sharma and Pallavi Singh. The show ‘opened’ on 25 September and was to be on display till 25 October, but the show has since been extended till 30 November 2020.

Located within the picturesque art complex, Triveni Kala Sangam, New Delhi, I visited the gallery to view the exhibition on two separate occasions. The first occasion was prompted by a visit to Delhi by Banaras-based fellow artist Padmini Mehta and we got together for a bite at the Triveni Terrace café, with another artist Juhi Kumar joining us for a socially distanced reunion. The second visit was when my co-founder at artamour Ranjan Kaul expressed a desire to see the show and meet up as well. These two have been the only instances when I’ve felt confident enough to step out to visit an art gallery since the pandemic broke out. Much of it has to do with Tariq Allana’s management of the gallery; his regular presence gives the assurance that the guidelines will be strictly followed and the visitors will be safe. On my first visit I had the opportunity to interview him in the gallery, the show and the artists. This is what he told me:

“Mr Ebrahim Alkazi had this vision of truly integrating the arts: the visual and performing arts. Mrs Roshen Alkazi had been managing the Black Partridge gallery and Mr Alkazi was at the helm of affairs at the National School of Drama before they opened Art Heritage to promote young and emerging artists. Starting from the first show in 1977 of MF Hussain, followed by SH Raza, Tyeb Mehta, Arpita Singh, Nalini Malani, and Bharti Kher among others over the years, the philosophy of focusing on the promotion of not- so established artists has been reflected in the series of shows that have been organized over the years.”

Elaborating on the selection and design for the show, Tariq added, “On the Threshold of Time was initiated eight years ago by Mrs Amal Allana, the Gallery Director, to take this idea right to the college level. There is a clear, democratic process of submission in place where the applicants are expected to submit their CV, Artist Note, and 15-20 images of their artworks. The CV gives an idea of the background of the artists, the residencies they’ve attended, and the exposure that they’ve had. The artist note gives an insight into how the artist thinks. The works of course speak for themselves. A combination of these three things is the consideration for the final selection. The selection and display is usually under the guidance of Mrs Allana. The exhibition design process starts from the scratch well in advance with a complete layout simulated digitally on SketchUp beforehand. This allows us to not only pre-plan everything including the display but also any fabrication that needs to be incorporated and designed in time for a glitch-free exhibition setup.”

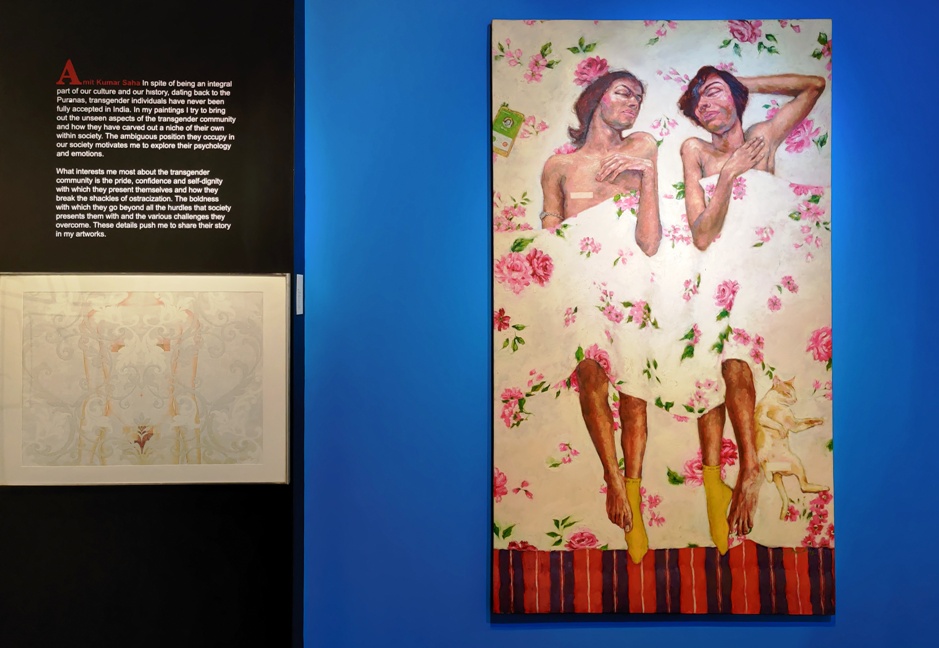

This eighth edition of On the Threshold of Time is titled Unseen. Each edition has had a theme connecting the works and has been a selection criterion as well at times, like the previous shows in the past on the themes of Urbania, Politics, Environment, etc. Of the five featured artists in this show, Amit Saha and Pallavi Singh have been showcased earlier as well by Art Heritage. Amit has worked extensively with the transgender community as a muse over the last six years or so. When one looks at his works, there is an air of comfort overall despite a sense of awkwardness of the central figures. The transgender community remains on the fringes of the society with limited scope for an established identity. On a telephonic conversation with me, Amit explained,

“I used to draw them quite often to study human anatomy as I found it affordable. With time I started to look at them not just as figures for drawing and study but as individuals with character and identity. Over time, it helped me to form a special bond with them. But now I don’t need them to pose for me; I’m able to draw and paint them from memory. I try to show them as comfortable as possible in my creations and also try to remove the sexuality or gender identity from the works because it is their individuality that needs to stand for itself in the composition.”

The work that one sees first as one enters the gallery is Together Alone, one of Amit’s larger works. It has two transgender individuals sleeping on a bed under a floral sheet comfortably, with a cat sprawled across the sheet at the bottom right of the painting. The sex of the cat is deliberately obliterated as a rectangular box is strategically placed; much like the one used to filter nude content on a social media site. The nipples of the individuals are also blocked out in similar fashion. Another of his works that really caught my eye is Untitled, which has a group of transgenders with lit cigarettes, possibly in a café with an ashtray on their table, with a bearded man on the next table plugged into his mobile headphones. There is a board hanging behind them that says, ‘Open to All’. The use of colour, line and text strings together a narrative that is pleasing to the eye, provocative and easy enough to understand. The unseen aspects of the community, their ambiguous position in society, and the pride, confidence and self-dignity with which they present themselves despite their ostracization, has motivated the artist to share their story in his artworks. The display of Amit’s plein air, water colours did not seem to be part of the theme and his series as well, and I found them to be an awkward choice for inclusion. There is also a collage of portraits on embellished paper ID – Entity, almost as if celebrating their simple existence.

Together Alone by Amit Saha, 70 inches × 40 inches, Oil on Canvas, 2018

Untitled by Amit Saha, 18 inches × 25 inches, Acrylic on Paper, 2017

ID – Entity by Amit Saha, 23.5 inches × 19.5 inches, Drawing on Paper, 2017

Pallavi Singh’s works cover the theme of metrosexuality, the culture of grooming among males. Over the phone, Pallavi said,

“Male preoccupation with beauty has been widely seen in mythologies and fables of the West and India. The metrosexual subject in my paintings is not limited to any specific class or strata of the society; the phenomenon is not confined to the upper affluent classes, rather it has a widespread reach. My approach is more than just satirical. It is a sober, social observation which deals with experimentation in terms of one’s outward physical appearance. While grooming and beauty have been typically considered inherently feminine, I’m interested in exploring the sensitivities and nuances around this phenomenon and deconstructing them in the context of Indian mythology, time, space and culture. Mark Simpson, the British journalist, has been credited with coining the term metrosexual in the nineties. I was influenced by his writings and in 2012-13 we exchanged emails on the subject. Without the knowledge of the term, everybody grooms.”

She has used a wide range of techniques and mediums but usually there is an illustrative quality to the multiple frame works. Her works are diptychs (two panels), triptychs (three panels) and even include multiple panels (as many as six). Her work Hypno Bazaar is literally the word bazaar spelled out on six sheets of paper but with a parade of groomed men hypnotized with the use of mirrors detailed within the alphabets. The transparent quality of the strokes with the use of the limits of the alphabets being bordered, add to the grooming narrative. In the triptych Mardon Wali Baat, Work-I, the male body is featured blossoming amidst a flowering garden. There is also a hint of the fascination with the size and proportion for a perfectly groomed male body. For some reason, I was reminded of the title track of the TV serial The Jungle Book on a Hindi channel in the nineties, by the famous lyricist Gulzar, “Jungle jungle shor macha hai, pata chala hai, Chaddi pehan ke phool khila hai, phool khila hai” (There’s a shout across the jungle that a flower has blossomed, one that wears an underwear).

Another of her works which catches the eye is The Corona Time. It is like a poster from my schooldays, showing the daily life of a man in the current pandemic times. It depicts how, despite the lack of any kind of outing, the bald male (a recurring character in a number of her works) grooms on a daily basis, simply to go back to bed. In our conversation, she also indicated that she is exploring the concept of grooming more as an aesthetic understanding than as a concept of mere cleanliness or hygiene. The pandemic compelled her to slow down because of fewer art materials available to her and her inability to access her muse and inspirations that she use to gather from her movements out of her home, which have been obviously hindered. She has meanwhile been applying for grants in the current situation and has also participated in a Michigan-based virtual exhibition.

Hypno Bazaar by Pallavi Singh, 29.5 × 21.5 inches each (six sheets together),

Mixed Media on Paper, 2020

Mardon Wali Baat, Work-I by Pallavi Singh, 29.5 × 21.5 inches each (Triptych),

Mixed Media on Paper, 2020

The Corona Time by Pallavi Singh, 21.5 × 15 inches, Acrylic on Paper, 2020

In contrast to Amit and Pallavi, who’ve acted somewhat as anthropologists, capturing people (transgender) or activities (male grooming) around us that go unseen, Tarun Sharma and Natasha Sachdeva use their own body and experiences to create an empathetic body of experiential works. Tarun has struggled with a recent bout of a serious respiratory condition. Tariq mentioned that one of the most haunting things said by Tarun during a video that they were making for the gallery’s channel was that “everybody has their own state of helplessness”. Once he recovered, Tarun’s perspective changed and he started to notice many things that we simply ignore as we go about our lives. During our telephonic conversation, he added,

“There are so many people on the streets and we simply walk past them. Knowingly or otherwise, we ignore them. By creating these works and displaying them in an art gallery, I want to acknowledge their existence. They are largely neglected by society but I want to bring their stories and their plight into focus with my series. I was completely bedridden for three months. Once I recovered, I found myself to be more empathetic, sensitive and observant than before, especially towards street dwellers who I encounter on my regular commute. I started reaching out to them, having conversations with them. I started questioning my privileges and decided to use my art as a way to contextualize what is happening around me. I am presently working further on the ‘Helplessness’ project that I’d begun work on during my scholarship period at Manhattan Graphics Center, New York. I’ve also resumed my Lalit Kala scholarship granted by the Ministry of Culture and researching on options to participate in Biennale/Triennale and so on, so that my works can travel.”

Tarun’s works feel very autobiographical in nature. They have a strong essence of his personal being and his vision in the most obvious and relatable terms. Mezzotint prints like 9pm on that bridge are dark, small in size and they force the viewer to come up close to the work to decipher the tale within. Beating Addiction has multiple snippets of the artist superimposed on his screaming self-portrait. Again, the viewer is caught with the darkness and the apt use of detailing; unable to step away or ignore the imagery. His paintings, which are part of the series Destitution and Helplessness, occupy a separate wall, with several works put together in a sort of collage/grid. The background surface and the clothes/coverings are in flat colours while the exposed body parts are worked upon in detail. The face, hands, feet, midriff are all detailed and the expressions are generally of sleep, almost out of exhaustion. The feeling of helplessness is transmitted quite strongly and doesn’t go unnoticed. The works leave a lasting impression, forcing one to look at similar people one encounters along the road in our daily lives.

9 pm on that Bridge by Tarun Sharma, 4.5 inches × 7 inches Mezzotint print, 15 editions, 2020

Beating Addiction by Tarun Sharma, 48 inches × 48 inches, Woodcut and Etching on Paper, 2018

Destitution and Helplessness Series by Tarun Sharma, approx. 25 inches × 18 inches each,

Mixed Media on Gessoed Paper, 2018. Photo credit: Aakshat Sinha

Natasha Sachdeva too uses the depiction of the body to stimulate the viewer’s mind, though it is not necessarily one to cause discomfort, rather once seen it becomes difficult to body-shame anyone. The muse is the artist herself; she draws herself in the flesh without any covering to hide the natural body shape and ‘baggage’ as it were. The use of the undergarments in a distinct variety of colours and styles only highlights the variety the women wear in comparison with men. As she expressed in our conversation over the phone,

“My water colours trace the form of large women with baggage and bulges. My medical condition has resulted in my gaining a lot of weight. There is an ideal figure that everyone compares with and the judgment led to me to shed a lot of weight suddenly. This left me traumatized and I started to question the ideals set by society. I paint large women – unapologetically. We are asked to be comfortable in our skin but then we are at the same time judged by the skin’s colour, flawlessness and texture. I paint the skin with all the tags, moles and blemishes as they are. While painting the skin and the feminine body in its reality, I also noticed the bright colours, prints and styles of women undergarments. I started to question if this was simply for others to appreciate and why men’s undergarments did not have a similar variety. I’ve been posing myself such questions and reflecting on similar concerns of late as I try to concentrate on working with a rigorous regime at the Garhi studios as part of the Lalit Kala scholarship. The pandemic has been a difficult time but it has allowed me to paint myself all the more.”

Natasha’s works are explorative and yet defining. Her set of four works, These Bulges Are Not Mine, depict a body that is testing its own elasticity, the folds and the bulges that sag. The works are small and yet they catch the eye; they compel one to compare them with the preconceived ‘set’ understanding of the ideal feminine figure. This is the reality, unabashedly. The work Age is Just a Number? – Net and Laces, has the profile of a seemingly aged body with sagging muscles and flesh; skin no longer taut; belly larger than the breast and the hips; breaking all traditions of the ideal body type to be featured in an artwork.; and yet, profoundly simple. A fact. Another set of 12 small works, Balancing my Hormones! has the artist reflecting on the different views of her body directly and in the mirror. The colours used are fresh when depicting the undergarments while earthy for the skin tone and texture. There is a sense of nudist reflection of the self: looking at the self, first questioningly, judgmentally, before becoming comfortable with what one sees.

These Bulges Are Not Mine by Natasha Sachdeva, 5 × 7.5 inches each, Water colour on paper, 2019

Age is Just a Number? – Net and Laces by Natasha Sachdeva, 20 × 30 inches,

Water colour on paper, 2020

Balancing my Hormones! by Natasha Sachdeva, 4.5 inches × 3.5 inches each,

Water Colour on Paper, 2019

Bhuwal Prasad is the senior-most of the group; he’s been practising since 2010 and his works are quite large. They occupy not only the largest wall but an extension as well. His works are surrealistic and dream-like. There is a variety of his work on display with some from his earliest period (2011) to the latest (2019) which gives a sense of progression of form and style. In our telephonic conversation he stated,

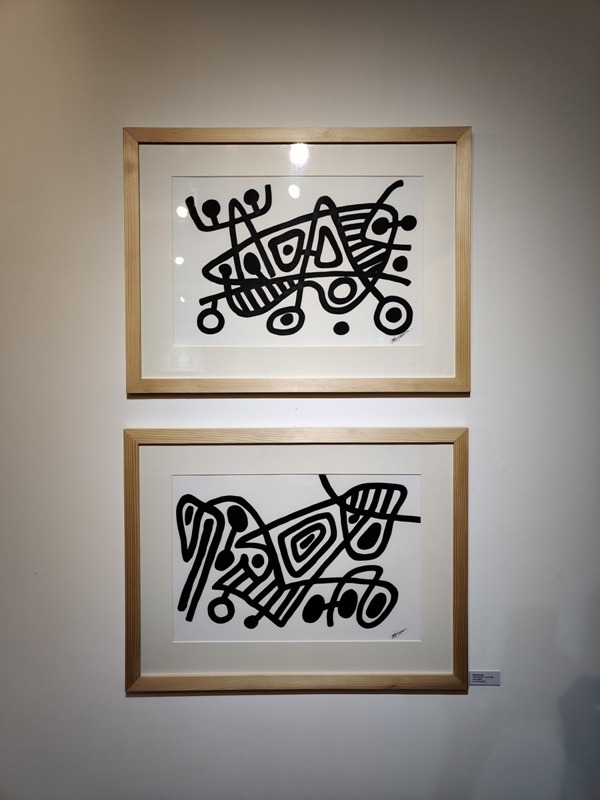

“I always loved to draw. In my initial works I used a combination of acrylic and charcoal on canvas. Tribal Convention is with that style. The works were generally quite dark and I got a lot of feedback to make them livelier. I experimented with bright colours and tribal inspirations. My diptych work Tribally Masquerade is from that period. From 2018 onwards I started to again experiment and started reducing the elements till I came down to just the lines. Insect Appules – III is a recent work. Of late, I've been experimenting and innovating further with the medium that I’m using. I’m trying metal sculptures, plywood, etc. What I depict is essentially my dreams, the unseen.”

Tribal Convention by Bhuwal Prasad, 96 inches × 360 inches (five tiles together),

Mix Media on Canvas, 2011

Tribally Masquerade by Bhuwal Prasad, 96 × 144 inches (Diptych), Acrylic on Canvas, 2014

Insect Appules – III by Bhuwal Prasad, 15 inches × 22 inches, Ink on Paper, 2019

I found the large works from his earlier period most appealing. They are dark but still have a freshness and emotive quality about them. There are a number of elements within – human, animals, and include a demonic presence among many other things. They are pure expression and open to multiple interpretations. His later work which is bright, loud and easy to discern has small repetitive motifs of birds, animals, etc camouflaged in the background with stylized human figures in the foreground. This distinction of the foreground and the background is clearly more pronounced than before. His 2019 works remind one of the cave squiggles that use a minimum number of strokes, almost a continuous black line that traverses on a significantly reduced paper size. What is interesting to see of course is the journey of the artist and his art over the last decade.

The exhibition write-up states,

“Taken together, works in Unseen remind us that an artist’s journey begins from the self, either through a look within or a commentary on what is immediately around them. It is in such perspectives where a worldview and a narrative develops, and affords us, the audience, a glimpse into the artistic process.”

I fully endorse the statement. The display itself has always been the high point of all shows at Art Heritage because the attention to detail by everyone involved adds to the experience of viewing a complete show. There is attention to space and layout which is customized to the need for each show, the flow of the artworks and artists through the exhibition, the visual juxtaposition of the different artworks wherever one may stand and view from, the colour of the walls as support/contrast to each set of the artworks, and the excellent use of lights (although not so much in the case of small, really dark works with glass as in the case of Tarun’s Mezzotints).

Photos from the exhibition courtesy of Aakshat Sinha

The gallery is well lit, airy and importantly, well sanitized and quite safe to visit. On both occasions I found no more than two or three visitors who were allowed access the gallery. There is a sanitizer in place at the entrance. These conditions are exceedingly becoming important criteria for selecting which galleries to visit. The artworks obviously have to be good enough, as they are at this show, to motivate visitors in these Covid times. For those of you who would like to avoid venturing out, you can view the show online by logging onto Art Heritage’s handle on Artsy.

(Artwork images are courtesy of Art Heritage.)

Also read reviews by Aakshat Sinha:

Aakshat Sinha is an artist and curator. He also writes poetry and has created and published comics. He is the Founding Partner of artamour.

Comments