Of Mutation, Refuse and Other-worldly Creatures

- Ranjan Kaul

- May 17, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: May 18, 2023

by Ranjan Kaul

The ongoing parallel exhibitions at Anant Art gallery in Noida features the expressive works of two courageous young artists – Niroj Stapathy and Aditya Puthur – whose curious practices, though vastly dissimilar, share common ground in certain ways.

The gallery note gives an insight into the rationale of exhibiting the two artists together: “Anant Art is pleased to introduce 6B Projects, a year-round exhibitions and programming platform for artists. We are thrilled to mark this occasion with a showcase of two distinct practices that enquire into the cadavers of modernity, entangling entropy and refuse in precise and undeniable compositions and assemblages—Niroj Satpathy’s Dhalav and Aditya Puthur’s The Place Called Body.” While Niroj’s part of the exhibition has been curated by Shankar Tripathi, Aditi Ghildiyal has curated Aditya’s section.

Niroj’s imaginative drawings, sculptural figurines, and elaborately constructed installations and assemblages of found objects, trash and decomposed waste, diligently accumulated over time, tell many stories. On the other hand, Aditya witnesses surgeries in real time to explore the mutability of the body by observing intimately the internal organs. The common thread that binds them is that the works of both artists assault our sensibilities, evoking strong and visceral emotions. Because I personally find Niroj’s work particularly fascinating and got a chance to speak with him at length over multiple sessions, this review primarily focuses on his art, not that Aditya’s work is any less engaging.

Dhalav by Niroj Satpathy

When crossing a landfill our instinctive reaction is to hold our breath and look away from the mucky mountain of monstrosity. But when someone makes a deliberate choice to work in a hideous and putrid environment like that, then it immediately piques our interest. A graduate of BK Art College and Utkal University of Culture, Odisha, Niroj has been involved with various camps, residencies, public art projects, exhibitions and collaborative projects, including the most recent, ‘Is the Image Even Human?’ at Instituto Cervantes, New Delhi (2023).

When Niroj moved to Delhi in 2012, a sight he couldn't help but notice was the mountainous dumping ground, shaped like undulating hills, at Ghazipur near his home, which he sardonically refers to as the “crown of Delhi”. Horrified by the sight, he felt compelled to investigate closely the site and other landfill and dumping grounds. And so he took up the extremely demanding assignment of a supervisor at landfill sites for a solid waste management company which had a tie-up with the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) where he managed collection and treatment of waste. The show is an outcome of his highly unusual experience at the landfills, especially during his nocturnal shifts in the shrill and forbidding silence of the night.

Prior to working with the solid waste management company, Niroj worked as a conservator with the Archaeological Survey of India, and is now teaching art. His creative practice spans across several mediums, scales and materiality, stemming from an abiding obsession with artefacts and discarded objects since he was fifteen. He says he has been inspired by the disruptive art practice of Marcel Duchamp, the creator of Fountain (a regular porcelain urinal, turned on its side and signed by the pseudonym R. Mutt), and Donald Judd, the American artist who rejected traditional painting and sculpture and built his work upon the idea of the object as it exists in the environment.

Left: The landfill top is flattened to allow for trucks to add to the mountain of waste

Right: Photograph of the Ghazipur landfill at night (Photos by Niroj Satpathy)

Niroj’s five-year experiential tenure at Delhi’s waste-disposal sites and the three major overflowing landfills, especially Bhalswa and Ghazipur (the third major one is at Okhla), led him to create the array of grotesque and yet bewitching assemblages, totemic drawings and sculptures on display. Almost 90 per cent of Niroj’s assemblages are made up of found objects sourced from Delhi’s landfills or those he purchased from the surrounding areas. (Those living in the surrounds, he informs me, run a regular business of first salvaging and then cleaning the waste before putting it out on sale.)

The sumptuous assemblages of quirky, bizarre and mysterious creations scream hysterically of things past as equally of the here and now, shocking us out of our passivity. As we enter into a dialogue with the artist, we are compelled to acknowledge the disturbing socio-ecological realities – the fears, anxieties, scandals, dangers that lurk in landfills – and the politics of waste, where the state machinery not only refuses to accept the gross mismanagement but, worse, even at times covers up. According to Niroj, there are about a hundred invisible inhabitants living in and off the landfills (no chance that census personnel will ever reach there) – migrants, outcasts, Bangladeshi refugees – co-existing with the innumerable rats, dogs, crows, cranes, eagles, and other scavenging creatures. They survive somehow or die unnoticed. Their deaths are seldom natural, and not because of starvation or the noxious air they breathe, but more often because of the accidental fires that erupt suddenly and blaze for days on end.

Parivar, 2014-23, Wood, dentures, horns, fibre cast, treated fungus, catechu stone

A landfill dweller (Photo by Niroj Satpathy)

Night Crawlers, 2014-2023, Installation with various assemblages

Seven members of a family of trans-beings are gathered for a family portrait in Parivar (2014-2023). Appearing like totems with horns and a couple with open-mouthed grins baring real dentures (unearthed from the landfills), the work is a manifestation of Niroj’s responsive imaginings (see also the photograph of one of the inhabitants given above). While the use of totems here and elsewhere for his other works (at times donning furs and feathers) is reminiscent of Red Indian tribes, Niroj is quick to clarify that his imagery also borrows from the tribal traditions of Odisha, his home state, as also Vishnu’s avatars.

Darkness plays strange tricks on us. World over people have grown up listening to ancient lore and mythology about ghosts, demons, monsters, vampires roaming in pitch-black nights. During lonely and fearful nights at the landfill, Niroj’s mind and senses, unsurprisingly, are assailed by macabre thoughts, nightmares, hallucinations, strange dreams. The huge installation of multiple assemblages, Night Crawler (see above), composed of mannequins, ropes, feathers, fur, wires, clocks, TV screens, statues, wooden cabinets, and what-have-you, appear as mighty commandos of another world ready for battle. Crawling out at night from the nether of gooey filth, they follow no rules, moving about imperiously with impunity. Stationed in the ambience of a purple haze they appear sinister and alluring at the same time (such as Project Narayan Industry and Project Bijliwala shown below), waging a metaphorical war, as it were, for supremacy over an empire where no one dare enter.

Night Crawler details.

Left: Project Naryana Industry 36.36666 . . . 2014-23, Mannequin, artificial feather, tripod stand, light, treated fungus, and other found objects

Right: Project Bijliwala 95444.444 . . . 2014-23, Fuller’s earth, tripod stand, iron sticks, mannequin, artificial fur, catechu stone, and other found objects

Tha 0 – Take a round, 2014-2023, Panel paintings, fuller’s earth, table clocks, ivory, wooden tonga,

and other found objects

Falana-Dhimkana, 2014-2023, Found objects from various dumping sites

The nuanced installation titled Tha 0 – Take a Round consists of art objects arranged at multiple levels to mimic the undulating landfill against the backdrop of abstract paintings made on papier-mâché panels prepared from organic waste, with a ferocious creature rearing its ugly head. While the heavily textured paintings are evocative of the slime and gook at the sites, the installation is suggestive of socio-religious and political dynamics and events down the ages. While the hanging clocks look back in time, a wretched figure is down on his knees, unable to drag the heavy baggage of the civilizational tonga. In a far corner, a temple sits atop a high stool, a reminder of the omnipresence of religiosity even as a lamp placed on a dark formation, looks forlorn, with an extinguished wick.

Falana-Dhimkana is a mammoth cabinet of shelves crammed with curios and souvenirs ranging from taxidermist animals and strange-looking dolls to cameras, daggers and pitchers, including a shelf lined with tall bottles filled with the crystallizing polluted waters of the river Yamuna. The objects have a universality and could belong to any time period with no hierarchy or nationality.

Detail shots of Falana-Dhimkana

There are several of Niroj’s drawings and other sculptural assemblages on display. The ones that also caught my fancy include an elongated arm with prickly ends titled Empty Hand; a statue with feathers encased in an open cabinet (Landfill Goddess), cast of a dark beastly form lying on its side on a trunk (with burnt red marks); Kasabpura Butcher House of assemblages simulating hanging carcasses and the cast of a beastly form (with red burn marks) lying on its side on a trunk; and a painting on glass titled Ranjit Nagar Nale ka Suer. He says he consciously created many of his sculptural works using multani mitti (Fuller’s earth, sourced from Afghanistan and Pakistan) to suggest the universal character of what finds its way in the landfills.

Drawings by Niroj Satpathy

Clockwise from top:

Kasabpura Butcher House, 78.6666 . . . , 2014-23, Artificial fur and feathers, fibre cast, jute ropes, fuller's earth, leather, LED lights, wooden spindle, plaster of paris, and other found objects;

Detail of Kasabpura Butcher House (photo by Ranjan Kaul);

Empty Hand, Fuller’s earth, stone, thorns, fibre cast hand;

Ranjit Nagar Nale ka Suer, 2014-2023, Painting over glass, sea shells, 20 inches in diameter

The array of Niroj’s explorations using found objects have a layered and complex dimensionality and ramifications. They shake us out of our unconcern towards the life-threatening toxicity and pollution of the overflowing landfills that seem to have gone out of control like the Night Crawlers. At the same time, we see the artist creating new myths with far-reaching implications in relation to our mindless consumerism, the politics of waste and identity, and so on.

The Place Called Body by Aditya Puthur

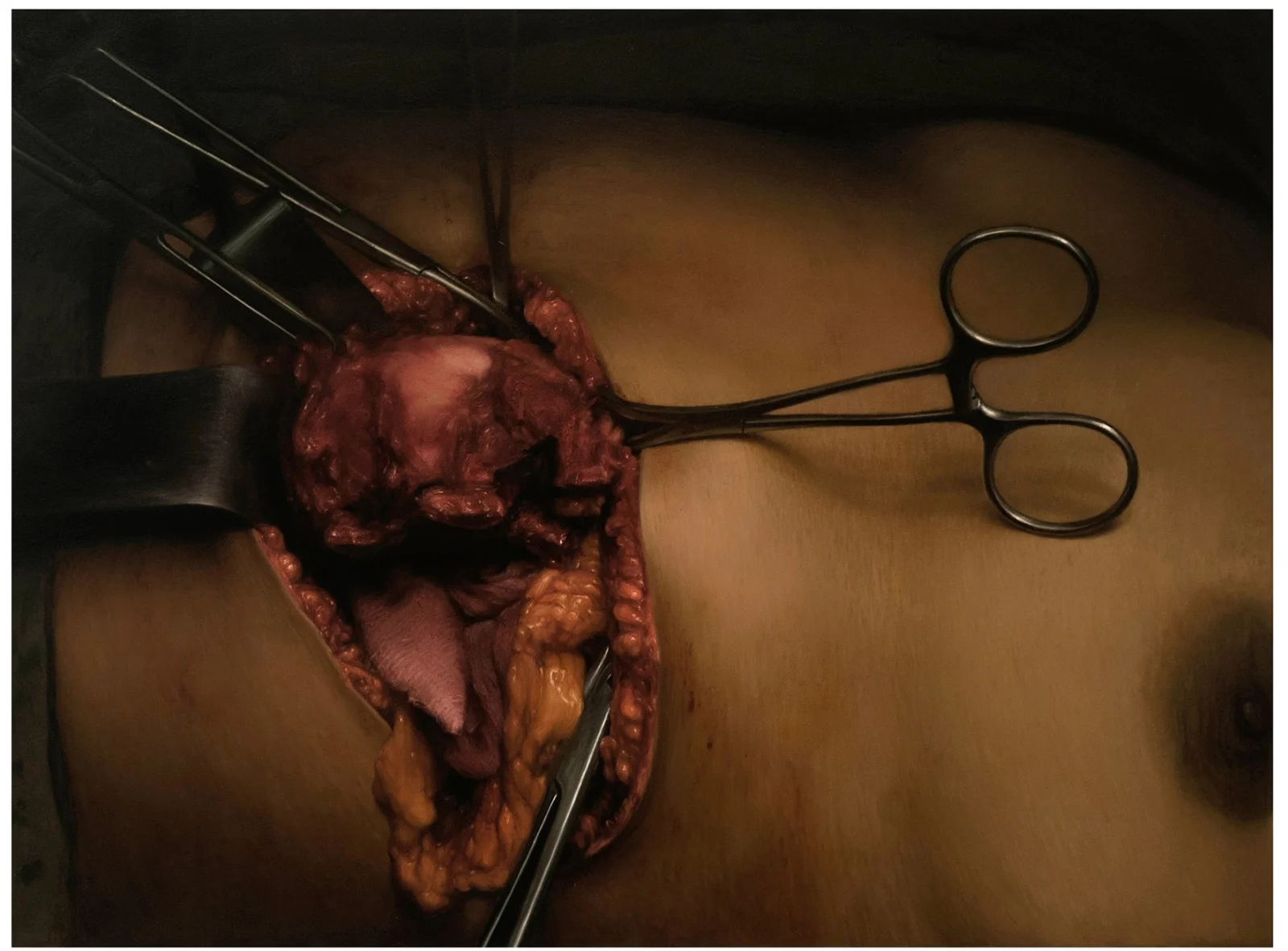

Transforming the body parts into a muse is a rare thing. Initially prompted by a critical surgery of a loved one, Aditya investigates the body by documenting live surgeries, consulting medical literature, surgeons and, pathologists and arrives at the conclusion that the body is a constantly mutating landscape. Questioning the accepted notion that the body is mere flesh and blood, he asserts that it is way more – an ever-changing terrain of decay, disease and death, and a manifestation of our consciousness. Using hyper-realistic imagery rendered through traditional oil painting techniques, his works hark back to the genre of medical imagery such as Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp and Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic. He gets under the skin, literally, folded back and pinned up for an invasive surgery, to reveal the throbbing and pulsating internal organs in Baroque-like, unfeeling detail, including showing the dissection tools, pins, hooks, scalpels. Besides the works that reveal the insides of the body, there are few that depict post-surgical stitches and marks on the body parts. The works are stark and unsettling, compelling the viewer to not turn away but become conscious of what is inside us.

Left: Unweaving the Rainbow 3, 2018, Oil on canvas, 54 x 72 inches

Right: Unweaving the Rainbow 5, 2019, Oil on canvas, 54 x 72 inches

Post-surgery, 2017, Oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches

Untitled, 2021, Oil on canvas, 12 x 16 inches

Besides his oil paintings, there are some other conceptual and exploratory works by Aditya on display, such as his ironical Designed to Last, where he proposes an evolutionary body form with a forward-tilt stature, a curved neck, an elongated vertebrae and backward knees, and Eye and I, where he also uses text and other mediums.

Top: Designed to Last, 2023, Graphite on paper, 15 x 13 inches

Bottom: Eye and I (set of 5), 2022, Oil on canvas, 2022, Glass vial, DNA, and text, 30 x24 inches

The visual practices of both Niroj Satpathy and Aditya Puthur point to the senseless obsession with beauty given the inevitability of mortality and decay, and challenge widely held notions of aesthetics and the erroneous assumption that the purpose of art is primarily for decoration. The exhibition demonstrates that good contemporary art can be disruptive, provocative and engaging, catalyzing discourse and action. The works of both artists are particularly relevant in the context of Indian contemporary art where a sizeable majority of artists and galleries seem to be mainly concerned with marketability and commodification. Anant Art needs to be commended and complimented for consistently promoting meaningful and socially relevant art that bucks this regrettable trend.

The exhibition at Anant Art gallery, Noida, will remain open till 20 May 2023.

(All images are courtesy of Anant Art gallery and the respective artists.)

Ranjan Kaul is a visual artist, art writer-critic, curator, author and Founding Partner of artamour. His works may viewed on www.ranjankaul.com and his insta handle @ranjan_creates.

Creativity at its best. Cathartic treatment of both waste and convalescent bodies post surgery . The review and images both invite the urge to actually see, touch, feel the exhibition in person. Kudos to the artists and gallery. Commendable review indeed.