Fearless Art: How South Asia’s Artists are Turning Protest into Institution

- artamour

- Oct 18, 2025

- 5 min read

By artamour special correspondent

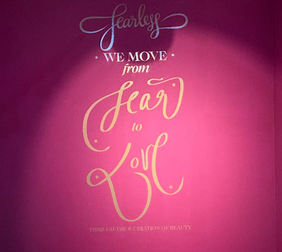

In the charged streets of Colombo, Dhaka, and Kabul, where voices have often been stifled and hopes deferred, a quiet but insistent revolution is underway — painted on walls, printed on posters, and shared across screens. Art of Liberation, a compelling exhibition presented by the Fearless Foundation, alongside Curatorial Advisor Myna Mukherjee, reimagines the intersection of art and activism across South Asia and its neighboring regions. Gathering visual testaments from Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, India, Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan, and Myanmar, the project transforms protest into poetry — and resistance into radical imagination.

At its heart lies a mission that feels both radical and restorative: to move from fear to love through the co-creation of beauty. It is a call to transform resistance into reimagination — to make space where silence once reigned, and to turn aesthetic practice into civic courage.

This vision is rooted in the work of Shilo Shiv Suleman, artist, activist, and Founder of the Fearless Collective and the Fearless Art Foundation. Over the last decade, Fearless has evolved from a movement of women painting street art murals in times of political fear to an ecosystem nurturing socially engaged art, archiving collective courage, and creating new models for cultural solidarity.

As Shilo reflects, “Fearlessness is not the absence of fear — it’s the decision to move forward with tenderness anyway. Through art, we create sanctuaries for beauty to resist erasure.”

Guiding the exhibition’s broader curatorial discourse is Myna Mukherjee, the show’s Curatorial Advisor and the Founder of Engendered, a transnational platform that builds bridges between art, pedagogy, and institutional practice based between New York and New Delhi.

Mukherjee, whose internationally renowned and celebrated multidisciplinary practice straddles activism and curatorial research, describes Art of Liberation as “a living archive of women’s collective courage — an evolving grammar of how beauty itself can be revolutionary.”

Art of Public Rupture: Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal

When governments collapse, artists often become the first historians of what follows. The section Art of Public Rupture gathers works born from political upheaval — the people’s movement in Sri Lanka, student uprisings in Bangladesh, and youth-led protests in Nepal. These images, drawn from streets, dormitories, and digital feeds, are less about aesthetic polish and more about civic immediacy.

In Sri Lanka, the murals and posters of the Aragalaya movement by Vicky Shahjehan channel a nation’s frustration into visual form. Painted on barricades and seaside tents, they transformed Galle Face Green into a site of collective dreaming — evidence that when institutions falter, creativity steps in to govern.

In Bangladesh, where student-led protests have long animated political discourse, the poster becomes both weapon and witness, as exemplified by the works of Ahsana Angona. Stenciled faces and handwritten slogans reappear as urgent acts of remembrance. And in Nepal, humor and satire are sharpened into tools of dissent, with Krisha Joshi lampooning the theatre of politics with irreverent precision.

To exhibit these works together is to honor what Mukherjee calls “resilience as an aesthetic — fragile, unpolished, and profoundly democratic.” These images do not simply document crisis; they construct an alternative archive, reminding us that when the state fails, art becomes both the witness and the remedy.

Art of Resonance: India and Pakistan

The section Art of Resonance brings together artists from India and Pakistan — two nations divided by history yet bound by shared anxieties about purity, faith, and belonging. Their posters, displayed in dialogue, challenge the politics of “othering” that has defined both countries since Partition.

In India, Shilo Shiv Suleman reworks national symbols — fists, lotuses, prayer motifs, and maps — into hybrid icons of tenderness and defiance. Her imagery, rooted in feminist spirituality, transforms the visual vocabulary of power into one of empathy. Across the border, Luluwa Lokhandwala reclaims Islamic calligraphy and Sufi ornamentation to critique sectarian violence and gendered erasure. Her work illuminates the contradictions between divine unity (tawheed) and social exclusion.

Seen together, their works form a powerful dialogue that collapses the distance between two nations often taught to fear each other. Here, the poster becomes a portable, democratic instrument of empathy — one that can be carried, copied, and shared by many.

As Mukherjee observes, “What emerges is not the binary of victim and perpetrator, but a shared anatomy of oppression and resilience.” Through these posters, artists reclaim the right to narrate their own image — and, in doing so, imagine a subcontinent where compassion itself becomes a political act.

Art as Resistance: Iran, Afghanistan, Myanmar

Further west and east of South Asia, the exhibition turns its gaze to Iran, Afghanistan, and Myanmar — nations where the fight for liberation has often been betrayed by renewed forms of control. Here, art is made under surveillance, smuggled through digital networks, or created within the intimate confines of domestic space.

In Iran, the aftermath of Mahsa Amini’s death ignited a movement whose aesthetic became inseparable from its politics. The rallying cry “Women, Life, Freedom” appeared in murals, posters, and graffiti, with works by Negin Rezaie marking each as a fragile yet fearless act of defiance. Artists, many working anonymously, reimagine the veil as symbol, flame, and wing — transforming restriction into flight.

In Myanmar, the imagery of the 2021 coup — the three-finger salute, Thanaka-painted faces, red ribbons — continues to circulate in clandestine street art and online protest posters, as seen in works by Chuu Nyu. Each image, though fleeting, declares that silence will not be normalized.

And in Afghanistan, where women artists have been erased from public life, resistance takes quieter forms. Zahra Khodadadi produces drawings on fabric, photographs taken in secret, murals painted over and repainted within private courtyards. These acts may never reach the gallery wall, but they echo the exhibition’s core premise: when regimes confiscate freedom, art confiscates fear.

From Street Movements to Institutional Imagination

What unites these regions is not uniform style but a shared urgency to institutionalize impermanence. The transition from spontaneous street art to sustained arts infrastructure marks a profound shift in the politics of cultural production across the Global South.

The Fearless Art Foundation, through initiatives like Art of Liberation, embodies this transition. By bridging grassroots movements with museums, archives, and pedagogy, it reframes protest as a long-term, intergenerational practice — one that carries memory, tenderness, and transformation into institutional space.

A Radical Grammar of Hope

Art of Liberation is not just an exhibition — it is an ethos. It proposes that beauty, often dismissed as decorative, can be a revolutionary force. That love, far from apolitical, can be a method of governance. And that art, when rooted in community, can transcend the temporal life of protest to become infrastructure — a living, breathing institution of care.

Across South Asia and its neighboring regions, artists are rebuilding the future not through policy or power but through imagination. They are teaching us that resilience is not passive endurance but active tenderness — the choice to keep creating even when everything else collapses.

As Mukherjee reflects, “Art is not made after resistance. It is resistance. Every brushstroke, every poster, every mural is a small rehearsal for the world we want to live in — one where fear no longer dictates who gets to be seen, heard, or free.”

In that rehearsal lies a quiet revolution — one that begins on the street, but refuses to end there.

Comments